الاثنين، 8 ديسمبر 2014

الأحد، 7 ديسمبر 2014

Thami's Monologue recorded

A Voice record of Thami's Monologue in "My Children! My Africa"Recorded by Hoda Fadl, A fourth year student at the faculty of Al-Alsun(Languages) - Department of English

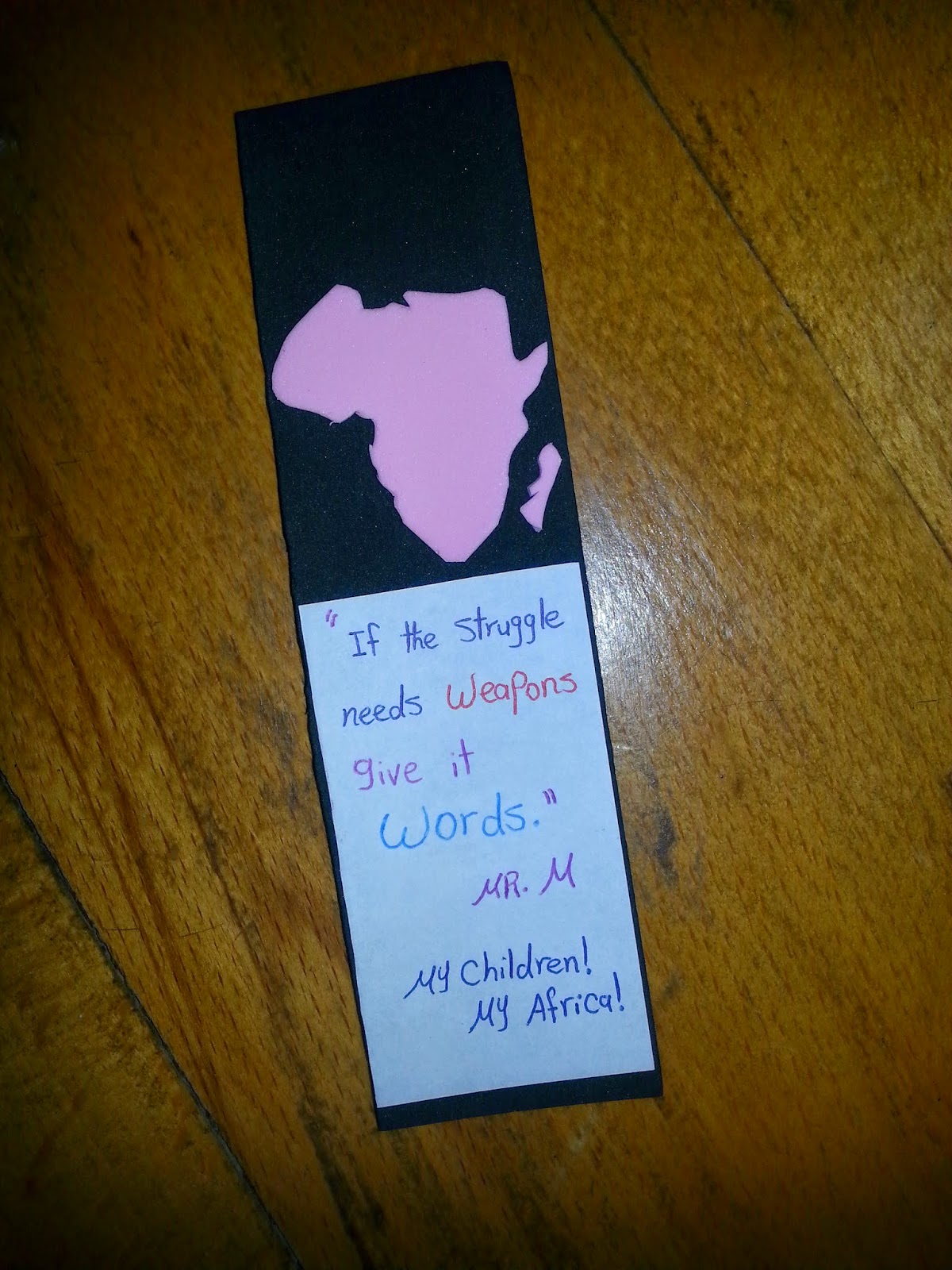

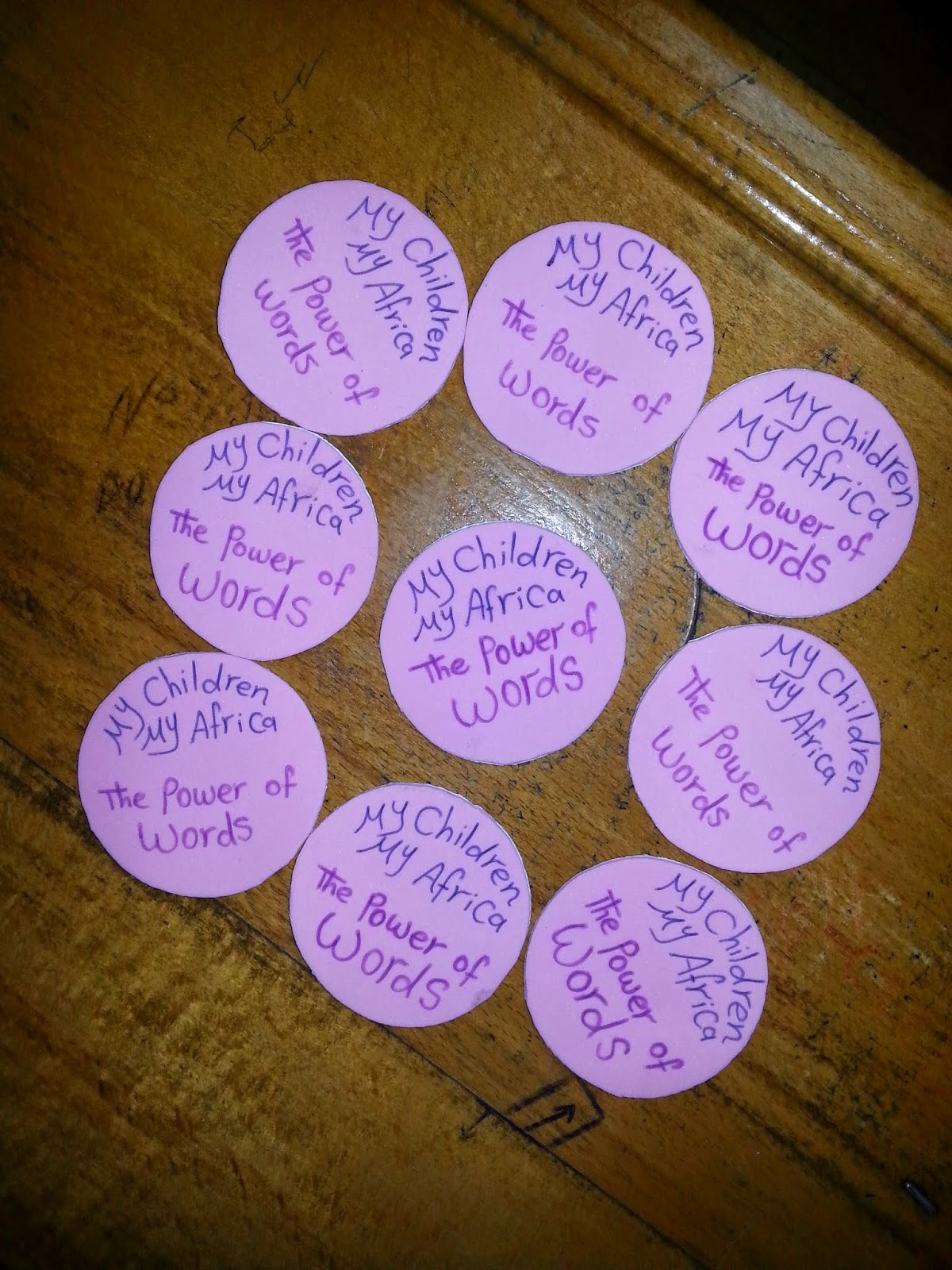

Quotations on The Power of Words in "My Children! My Africa"!

A sound track citing important quotations from the play on the Power of Words in "My Children ! My Africa! "

A soundtrack recorded by Huda Alaa, A fourth year student at the Faculty of Al Alsun (languages) - Department of English

السبت، 6 ديسمبر 2014

The Power of Words in "My Children! My Africa!"

My Children! My Africa!

By Adam Langer

MY CHILDREN! MY AFRICA!

Wisdom Bridge Theatre

To South African playwright Athol Fugard, language is perhaps the most important weapon in the struggle for political reform. At one point in his My Children! My Africa! Mr. M, a well-respected black teacher, holds up a rock in one hand and an English dictionary in the other. They both weigh about the same, he says, but a rock is only a rock and a dictionary carries the force of the entire English language.

The characters of My Children! My Africa! fight battles with words against a backdrop of political strife. Everywhere we see how words and phrases can be twisted to gain political advantage. "Beware," one character warns another. "Beware of the words that you use."

The play opens with a debate between two prize students: Thami Mbikwana, a master orator from a poor black township, and Isabel Dyson, a white student visiting from a neighboring school. Their debate over whether women should receive the same education as men is moderated by the brilliant Mr. M, who warns them that they should never let their argument devolve into a shouting match--that they should always rely on reason to express their views.

Mr. M plans to use these two as a team in an upcoming interschool competition on English literature. Isabel and Thami practice for the competition by quizzing each other on the works of Keats, Shelley, and Coleridge, engaging in some friendly one-upmanship. But the plans for a partnership crumble when Thami becomes part of a violent antiapartheid struggle and refuses to listen to Mr. M: Thami believes he may be an informer against the cause.

Fugard uses the struggle between the passionate Thami and the intellectual Mr. M, which Isabel witnesses and sometimes attempts to mediate, to illustrate two different approaches to effecting political change: emotion battles reason in polemical dialogues, a battle that drives the play to its tragic conclusion.

Fugard's brilliant characterizations make this play a fascinating excursion into the politics of South Africa. Each character's motives and statements are completely understandable in this political context. We sympathize with Mr. M's desire to use reason to fight the oppressive system, and yet we understand Thami's frustration with Mr. M's teachings and his need to do something more concrete. And we can understand Isabel's pain, caught between these two opposing forces.

The play is composed mainly of dialogues and long monologues that express each character's background, feelings, and desires. There is very little action. But the powerful emotions behind the characters' remarks make every speech and conversation a highly charged event. By the play's close we understand Mr. M's contention (and perhaps Fugard's) that sometimes words speak louder than actions.

Under Terry McCabe's direction, Wisdom Bridge Theatre's production of My Children! My Africa! retains all the power and emotion of Fugard's script. Ernest Perry Jr. as Mr. M, Tab Baker as Thami, and Michelle Elise Duffy as Isabel deliver compelling performances, their diction and dialects impeccable. There is not a dishonest moment in the entire evening. The performers' interactions are thoroughly believable, and you can see them savoring every word of the script.

Chip Yates's excellent scenic design allows us to move from a South African classroom to a ramshackle house with only a lighting change (devised by Michael Rourke). Like the play, this production seeks to appeal to both the mind and the heart. It succeeds on both levels.

Art accompanying story in printed newspaper (not available in this archive): photo/Roger Lewin--Jennifer Girard Studio.

http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/my-children-my-africa/Content?oid=878981

By Adam Langer

MY CHILDREN! MY AFRICA!

Wisdom Bridge Theatre

To South African playwright Athol Fugard, language is perhaps the most important weapon in the struggle for political reform. At one point in his My Children! My Africa! Mr. M, a well-respected black teacher, holds up a rock in one hand and an English dictionary in the other. They both weigh about the same, he says, but a rock is only a rock and a dictionary carries the force of the entire English language.

The characters of My Children! My Africa! fight battles with words against a backdrop of political strife. Everywhere we see how words and phrases can be twisted to gain political advantage. "Beware," one character warns another. "Beware of the words that you use."

The play opens with a debate between two prize students: Thami Mbikwana, a master orator from a poor black township, and Isabel Dyson, a white student visiting from a neighboring school. Their debate over whether women should receive the same education as men is moderated by the brilliant Mr. M, who warns them that they should never let their argument devolve into a shouting match--that they should always rely on reason to express their views.

Mr. M plans to use these two as a team in an upcoming interschool competition on English literature. Isabel and Thami practice for the competition by quizzing each other on the works of Keats, Shelley, and Coleridge, engaging in some friendly one-upmanship. But the plans for a partnership crumble when Thami becomes part of a violent antiapartheid struggle and refuses to listen to Mr. M: Thami believes he may be an informer against the cause.

Fugard uses the struggle between the passionate Thami and the intellectual Mr. M, which Isabel witnesses and sometimes attempts to mediate, to illustrate two different approaches to effecting political change: emotion battles reason in polemical dialogues, a battle that drives the play to its tragic conclusion.

Fugard's brilliant characterizations make this play a fascinating excursion into the politics of South Africa. Each character's motives and statements are completely understandable in this political context. We sympathize with Mr. M's desire to use reason to fight the oppressive system, and yet we understand Thami's frustration with Mr. M's teachings and his need to do something more concrete. And we can understand Isabel's pain, caught between these two opposing forces.

The play is composed mainly of dialogues and long monologues that express each character's background, feelings, and desires. There is very little action. But the powerful emotions behind the characters' remarks make every speech and conversation a highly charged event. By the play's close we understand Mr. M's contention (and perhaps Fugard's) that sometimes words speak louder than actions.

Under Terry McCabe's direction, Wisdom Bridge Theatre's production of My Children! My Africa! retains all the power and emotion of Fugard's script. Ernest Perry Jr. as Mr. M, Tab Baker as Thami, and Michelle Elise Duffy as Isabel deliver compelling performances, their diction and dialects impeccable. There is not a dishonest moment in the entire evening. The performers' interactions are thoroughly believable, and you can see them savoring every word of the script.

Chip Yates's excellent scenic design allows us to move from a South African classroom to a ramshackle house with only a lighting change (devised by Michael Rourke). Like the play, this production seeks to appeal to both the mind and the heart. It succeeds on both levels.

Art accompanying story in printed newspaper (not available in this archive): photo/Roger Lewin--Jennifer Girard Studio.

http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/my-children-my-africa/Content?oid=878981

A brief history of the African National Congress

A brief history of the African National Congress

Our struggle for freedom has a long history. It goes back to the days when the African people fought spear in hand against the British and Boer colonisers.

The ANC has kept this spirit of resistance alive! Over the last 80 years the ANC has brought together millions in the struggle for liberation. Together we have fought for our land, against low wages, high rents and the dompas. We have fought against bantu education, and for the right to vote for a government of our choice. This history is about our struggle for freedom and justice. It tells the story of the ANC

1. The African Kingdoms are defeated 1860s - 1900

White settlers from Holland first came to South Africa in 1652. many bitter struggles were fought over land and cattle. Although the African kingdoms lost land and cattle they were still independent some 200 years later.

But in the 1860s Britain brought large armies with horses, modern rifles and cannons, to take control of South Africa. The Xhosa who had fought nine wars of resistance against the colonisers, were finally defeated in 1878, after more than 100 years of warfare.

Led by Cetshwayo, the Zulu brought a crushing defeat on the British army at Isandhlwana in 1878, but were finally defeated at Ulundi by British reinforcements. Soon afterwards the British attacked and defeated the Pedi who had also remained independent for many years.

Leaders like Sukhukhune, Sandile and Cetshwayo were captured and imprisoned or killed. By 1900 Britain had broken the power of the African kingdoms and they then fell under the control of the colonial government. In 1910, Britain handed over this control to the Boer and British settlers themselves, when it gave them independence. The union of South Africa was formed with a government that recognised only the rights of white people and denied rights to blacks.

2. The ANC is formed - 1912

The wars of resistance ended with the defeat of Bambata`s rebellion. Africans had to find new ways to fight for their land and their freedom. In 1911, Pixley ka Isaka Seme called on Africans to forget the differences of the past and unite together in one national organisation. He said: "We are one people. these divisions, these jealousies, are the cause of all our woes today."

On January 8th 1912, chiefs, representatives of people`s and church organisations, and other prominent individuals gathered in Bloemfontein and formed the African National Congress. The ANC declared its aim to bring all Africans together as one people to defend their rights and freedoms.

The ANC was formed at a time when South Africa was changing very fast. Diamonds had been discovered in 1867 and gold in 1886. Mine bosses wanted large numbers of people to work for them in the mines. Laws and taxes were designed to force people to leave their land. The most severe law was the 1913 land Act, which prevented africans from buying, renting or using land, except in the reserves.

Many communities or families immediately lost their land because of the Land Act. for millions of other black people it became very difficult to live off the land. The Land Act caused overcrowding, land hunger, poverty and starvation.

3. Working for a Wage

The Land Act and other laws and taxes forced people to seek work on the mines and on the white farms. While some black people settled in cities like Johannesburg, most workers were migrants. They travelled to the mines to work and returned home to the rural areas with part of their wages, usually once a year.

But Africans were not free to move as they pleased. Passes controlled their movements and made sure they worked either on the mines or on the farms. The pass laws also stopped Africans from leaving their jobs or striking. In 1919 the ANC in Transvaal led a campaign against the passes. The ANC also supported the militant strike by African mineworkers in 1920.

However, some ANC leaders disagreed with militant actions such as strikes and protests. They argued that the ANC should achieve its aims by persuasion, for example, by appealing to Britain. but the appeals of delegations who visited Britain in 1914 to protest the Land Act and again in 1919 to ask Britain to recognise African rights, were ignored.

This careful approach meant that the ANC was not very active in the 1920s. The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) - a general union formed in 1919 - was the most active and popular organisation in rural and urban areas, at this time. The union won some major victories for its workers through militant actions. However, the ICU could not sustain itself, and in the late 1920s it collapsed.

Socialist organisations also began to organise black workers in the 1920s. The International Socialist League together with other socialist organisations formed the Communist Party in 1921. The Communist Party became the first non-racial political organisation in South Africa.

During the 1920s government policies became harsher and more racist. A colour-bar was established to stop blacks from holding semi-skilled jobs in some industries. It also meant that black workers were paid lower wages for unskilled work.

J.T. Gumede, was elected President of the ANC in 1927. He tried to revitalise the ANC in order to fight these racist policies. Gumede thought that the communists could make a contribution to this struggle and wanted the ANC to co-operate with them. However, in 1930, Gumede was voted out of office and the ANC became inactive in the 1930s undergo conservative leadership.

4. The ANC Gains New Life - 1940s

The ANC was boosted with new life and energy in the 1940s, which changed it from the careful organisation it was in the 1930s to the mass movement it was to become in the 1950s.

Increased attacks on the rights of black people and the rise of extreme Afrikaner nationalism created the need for a more militant response from the ANC. Harsher racism also brought greater co-operation between the organisations of Africans, Coloureds and Indians. In 1947, the ANC and the Indian Congresses signed a pact stating full support for one another`s campaigns.

In 1944 the ANC Youth League was formed. The young leaders of the Youth League - among them Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo - based their ideas on African nationalism. They believed Africans would be freed only by their own efforts. The Youth League aimed to involve the masses of people in militant struggles.

Many more people moved to the cities in the 1940s to work in new factories and industries. They began to from their own community organisations - such as the Squatter`s Movement - and trade unions. The militant ideas of the Youth League quickly found support among the new population of the cities. The Youth League drew up a Programme of Action calling for strikes, boycotts and defiance. It was adopted by the ANC in 1949, the year after the National party came to power. The Programme of Action led to the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s.

5. A Mass Movement is Born - 1950

The Defiance Campaign was the beginning of a mass movement of resistance to apartheid. apartheid aimed to separate the different race groups completely through laws like the Population Registration Act, Group areas Act and Bantu Education Act, and through stricter pass laws and forced removals.

"Non-Europeans" walked through "Europeans Only" entrances and demanded service at "White`s Only" counters of post offices. Africans broke the pass laws and Indian, Coloured and White "volunteers" entered African townships without permission.

The success of the Defiance Campaign encouraged further campaigns against apartheid laws, like the Group Areas Act and the Bantu Education Act.

The government tried to stop the Defiance Campaign by banning it`s leaders and passing new laws to prevent public disobedience. but the campaign had already made huge gains. It brought closer co-operation between the ANC and the SA Indian Congress, swelled their membership and also led to the formation of new organisations; the SA Coloured people`s Organisation (SACPO) and the Congress of Democrats (COD), an organisation of white democrats.

These organisations, together with the SA Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) formed the Congress Alliance.

The Congress Alliance came together to organise the Congress of the people - a conference of all the people of South Africa - which presented people`s demands for the kind of South Africa they wanted.

The demands called for the people to govern and for the land to be shared by those who work it. They called for houses, work, security and for free and equal education. These demands were drawn together into the Freedom Charter which was adopted at the Congress of the People at Kliptown on the 26th June 1955.

The government claimed that the Freedom Charter was a communist document. Communism had been banned by the government in 1950, so they arrested ANC and Congress leaders and brought them to trial in the famous Trason Trial. They also tried to prove that the ANC and its allies had a policy of violence and planned to overthrown the state.

In 1955 the government announced that women must carry passes. A huge campaign was mounted by women, countrywide. Women also led a militant campaign against municipal beerhalls. According to the law it was illegal for women to brew traditional beer. Police raided homes and destroyed home brewed liquor so that men would use municipal beerhalls. In response, women attacked the beerhalls and destroyed equipment and buildings. The women also organised a highly successful boycott of the beerhall.

There were many other community struggles in the 1950s. Resistance in the rural areas reached new heights. In many areas campaigns were led by the ANC against passes for women, forced removals and the Bantu Authorities Act. The Bantu Authorities Act gave the white government the power to remove chiefs they considered troublesome and replace them with those who would collaborate with the racist system.

The collaboration of chiefs with government officials was one of the causes of the Pondoland Revolt, a major event in the resistance by rural people. The Pondos also demanded representation in parliament, lower taxes and an end to Bantu Education.

The struggles of the 1950s brought blacks and whites together on a much greater scale in the fight for justice and democracy. The Congress Alliance was an expression of the ANC`s policy of non-racialism. This was expressed in the Freedom Charter which declared that South Africa belongs to all who live in it.

But not everyone in the ANC agreed with the policy of non- racialism. A small minority of members who called themselves Africanists, opposed the Freedom Charter. They objected to the ANC`s growing co-operation with whites and Indians, who they described as foreigners. They were also suspicious of communists who, they felt, brought a foreign ideology into the struggle.

The differences between the Africanists and those in the ANC who supported non-racialism, could not be overcome. In 1959 the Africanists broke away and formed the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Anti-pass campaigns were taken up by both the ANC and the PAC in 1960.

The PAC campaign began on the 21st March. People were asked to leave their passes at home and gather at police stations to be arrested. People gathered in large numbers at Sharpville in the Vaal and at Nyanga and Langa near Cape Town. At Sharpville the police opened fire on the unarmed and peaceful crowd, killing 69 and wounding 186.

The massacre of peaceful protestors at Sharpville brought a decade of peaceful protest to an end. On 30 March 1960, ten days after the Sharpville massacre, the government banned the ANC and the PAC. They declared a state of emergency and arrested thousands of Congress and PAC activists.

6. The Armed Struggle Begins - 1960s

The ANC took up arms against the South African Government in 1961. The massacre of peaceful protestors and the subsequent banning of the ANC made it clear that peaceful protest alone would not force the regime to change. The ANC went underground and continued to organise secretly. Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was formed to "hit back by all means within our power in defence of our people, our future and our freedom"

In 18 months MK carried out 200 acts of sabotage. But the underground organisation was no match for the regime, which began to use even harsher methods of repression. Laws were passed to make death the penalty for sabotage and to allow police to detain people for 90 days without trial. in 1963, police raided the secret headquarters of MK, arresting the leadership. This led to the Rivonia Trial where the leaders of MK were charged with attempting to cause a violent revolution.

Some ANC leaders - among them Oliver Tambo and Joe Slovo avoided arrest and left the country. Other ANC members left to undergo military training.

After the Rivonia Trial, the underground structures of the ANC in the country were all but destroyed. The ANC was faced with the question of how to bring trained soldiers back into the country to continue the struggle. However, South Africa was surrounded by countries that were very hostile to the ANC. Rhodesia, Angola and Mozambique were all controlled by colonial governments that supported the regime. MK would first have to make its way through those countries before it could reach home ground.

In 1967, MK began a joint campaign with Zapu, a people`s army fighting for the liberation of Zimbabwe. They aimed to find a route into South Africa by first crossing the Zambezi River from Zambia and into Zimbabwe, then marching across Zimbabwe through Wankie Game reserve, and crossing the Limpopo River into South Africa. While the Wankie Campaign gave MK cadres important experience in combat, it was clear that MK would have to find other ways of getting into the country. The ANC consultative conference at Morogoro, Tanzania in 1969 looked for solutions to this problem.

The Morogoro Conference called for an all-round struggle. Both armed struggle and mass political struggle had to be used to defeat the enemy. But the armed struggle and the revival of mass struggle depended on building ANC underground structures within the country. A fourth aspect of the all-round struggle was the campaign for international support and assistance from the rest of the world. These four aspects were often called the four pillars of struggle. The non-racial character of the ANC was further consolidated by the opening up of the ANC membership to non-Africans.

7. Workers and Students Fight Back - 1970s

During the 1960s, as a result of the banning of the liberation movement, there were few signs of resistance. The apartheid system grew stronger and extended its control over all aspects of people`s lives. But, despite the lull, people were not prepared to accept the hardships and oppression of apartheid. In the 1970s workers and students fought back against the system. their struggles changed the face of South Africa.

From about 1970 prices began to rise sharply, making it even more difficult for workers to survive on low wages. Spontaneous strikes resulted: workers walked off the job demanding wage increases. The strike began in Durban in 1973 and later spread to other parts of the country.

Student anger and grievances against bantu education exploded in June 1976. Tens of thousands of high school students took to the streets to protest against compulsory use of Afrikaans at schools. Police opened fire on marching students, killing thirteen year old Hector Petersen and at least three others. This began an uprising that spread to other parts of the country leaving over 1,000 dead, most of whom were killed by the police.

Many Soweto student leaders were influenced by the ideas of black consciousness. The South African Students Movement (SASM), one of the first organisations of black high school students, played an important role in the 1976 uprising. There were also small groups of student activists who were linked to old ANC members and the ANC underground. ANC underground structures issued pamphlets calling on the community to support students and linking the student struggle to the struggle for national liberation

8. The Struggle for People`s Power - 1980s

In the 1980s, people took the liberation struggle to new heights. In the workplace, in the community and in the schools, the people aimed to take control of their situation. All areas of life became areas of political struggle. These strugglers were linked to the demand for political power.

Thousands of youths flooded the ranks of MK after the 1976 uprising. The violence used by the security forces to quell the uprising made the youths determined to come back and fight. The 1976 uprising also led the regime to change its strategy. For the first time reforms were introduced to apartheid. These aimed to win some support from the black community, but without making substantial changes. at the same time the military was greatly strengthened. They could use greater force and repression against people and organisations who ere considered revolutionary. Through the State Security Council and a network of other structures, the military also gained control over the most important decisions of government. This combination of reform and repression, the NP government described as winning the hearts and minds of black South Africans.

However, the reforms proposed by the government, such as the Tricameral Parliament and Black Local Authorities in African Townships, were totally rejected and only gave rise to greater resistance.

In the 1980s community organisations such as civics, students and youth organisations and women`s structures began to spring up all over South Africa. This was a rebirth of the mass Congress movement and led to the formation of the United Democratic Front.

One of the biggest organisations formed at this time was the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) with branches in towns and cities throughout South Africa. In many cases civic organisations developed out of parent - student committees which had been formed to support education struggles. Massive national school boycotts rocked the townships in 1980 and again in 1984/5.

Worker organisation and power also took a major step forward with the formation of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985. Cosatu drew together independent unions that had begun to grow in the seventies. Cosatu committed itself to advancing the struggles of workers both in the workplace and in the community. 1987 saw the highest number of strikes ever, including a strike by over 300,000 mineworkers.

In 1985, the ANC called on township residents to make townships ungovernable by destroying the Black Local Authorities. Councillors and police were called on to resign. Municipal buildings and homes of collaborators were attacked. As the administrative system broke down, people established their own democratic structures to run the community, including street committees and people`s courts. An atmosphere of mass insurrection prevailed in many townships and rural towns across the country during 1985 and 1986. Mass struggles and the armed struggle began to support one another. Troops and police who had moved into the townships at the end of 1984 engaged in running battles with youths - armed with stones and petrol bombs - in an effort to re-establish control.

As resistance mounted, the regime became more vicious. A state of emergency was declared over many parts of the country in July 1985. It lasted for six months, and then in June 1986 a national emergency was declared, that lasted until 1990. The states of emergency were used to detain over 300,000 people, among them children, and to ban the UDF and its affiliates from all activity. Cosatu was restricted from political activity.

Secret government units killed activists and bombed their homes. The South African Defence Force (SADF) led raids into neighbouring countries to destroy ANC bases. These raids were part of a general strategy to destabilise neighbouring governments that offered the ANC support. The South African government gave extensive support to bandit organisations like Renamo in Mozambique and Unita in Angola.

The struggle for people`s power in the 1980s shook the foundations of the bantustan system. The regime tried desperately to save it by supporting vigilante groups and suppressing popular resistance.

In Natal, the struggle for people`s power was met with violence by Inkatha warlords who were opposed to the growth of community organisations. civic and youth organisations and Cosatu were opposed to the undemocratic practices of Inkatha and its ties to the KwaZulu government. The conflict has led to a bitter war in Natal, where thousands have lost their lives. Today there is evidence that the apartheid government gave money to Inkatha to fight the ANC, and that the South African Police and the KwaZulu Police have played active roles in this war.

9. The ANC is Unbanned

In spite of detentions and bannings, the mass movement took to the city streets defiantly with the ANC and SACP flags and banners. The people proclaimed the ANC unbanned. In February 1990, the regime was forced to unban the ANC and other organisations.

By unbanning the ANC, the regime indicated for the first time, that it might be prepared to try and solve South Africa`s problems peacefully, through negotiations.

After its unbanning the ANC began to establish branch and regional structures of its members. Regional and national membership was elected. At its national conference inside the country since 1959, the ANC restated its aim to unite South Africa and bring the country to free and democratic elections.

At the 1991 National Conference of the ANC Nelson Mandela was elected President. Oliver Tambo, who served as President from 1969 to 1991 was elected National Chairperson. Tambo died in April 1993 after serving the ANC his entire adult life.

The negotiations initiated by the ANC resulted in the holding of historic first elections based on one person one vote in April 1994.

The ANC won these first historic elections with a vast majority. 62,6% of the more than 22 million votes cast were in favour of the ANC.

On the 10th of May 1994 Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the President of South Africa. The ANC has been in power ever since

http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=206

Our struggle for freedom has a long history. It goes back to the days when the African people fought spear in hand against the British and Boer colonisers.

The ANC has kept this spirit of resistance alive! Over the last 80 years the ANC has brought together millions in the struggle for liberation. Together we have fought for our land, against low wages, high rents and the dompas. We have fought against bantu education, and for the right to vote for a government of our choice. This history is about our struggle for freedom and justice. It tells the story of the ANC

1. The African Kingdoms are defeated 1860s - 1900

White settlers from Holland first came to South Africa in 1652. many bitter struggles were fought over land and cattle. Although the African kingdoms lost land and cattle they were still independent some 200 years later.

But in the 1860s Britain brought large armies with horses, modern rifles and cannons, to take control of South Africa. The Xhosa who had fought nine wars of resistance against the colonisers, were finally defeated in 1878, after more than 100 years of warfare.

Led by Cetshwayo, the Zulu brought a crushing defeat on the British army at Isandhlwana in 1878, but were finally defeated at Ulundi by British reinforcements. Soon afterwards the British attacked and defeated the Pedi who had also remained independent for many years.

Leaders like Sukhukhune, Sandile and Cetshwayo were captured and imprisoned or killed. By 1900 Britain had broken the power of the African kingdoms and they then fell under the control of the colonial government. In 1910, Britain handed over this control to the Boer and British settlers themselves, when it gave them independence. The union of South Africa was formed with a government that recognised only the rights of white people and denied rights to blacks.

2. The ANC is formed - 1912

The wars of resistance ended with the defeat of Bambata`s rebellion. Africans had to find new ways to fight for their land and their freedom. In 1911, Pixley ka Isaka Seme called on Africans to forget the differences of the past and unite together in one national organisation. He said: "We are one people. these divisions, these jealousies, are the cause of all our woes today."

On January 8th 1912, chiefs, representatives of people`s and church organisations, and other prominent individuals gathered in Bloemfontein and formed the African National Congress. The ANC declared its aim to bring all Africans together as one people to defend their rights and freedoms.

The ANC was formed at a time when South Africa was changing very fast. Diamonds had been discovered in 1867 and gold in 1886. Mine bosses wanted large numbers of people to work for them in the mines. Laws and taxes were designed to force people to leave their land. The most severe law was the 1913 land Act, which prevented africans from buying, renting or using land, except in the reserves.

Many communities or families immediately lost their land because of the Land Act. for millions of other black people it became very difficult to live off the land. The Land Act caused overcrowding, land hunger, poverty and starvation.

3. Working for a Wage

The Land Act and other laws and taxes forced people to seek work on the mines and on the white farms. While some black people settled in cities like Johannesburg, most workers were migrants. They travelled to the mines to work and returned home to the rural areas with part of their wages, usually once a year.

But Africans were not free to move as they pleased. Passes controlled their movements and made sure they worked either on the mines or on the farms. The pass laws also stopped Africans from leaving their jobs or striking. In 1919 the ANC in Transvaal led a campaign against the passes. The ANC also supported the militant strike by African mineworkers in 1920.

However, some ANC leaders disagreed with militant actions such as strikes and protests. They argued that the ANC should achieve its aims by persuasion, for example, by appealing to Britain. but the appeals of delegations who visited Britain in 1914 to protest the Land Act and again in 1919 to ask Britain to recognise African rights, were ignored.

This careful approach meant that the ANC was not very active in the 1920s. The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) - a general union formed in 1919 - was the most active and popular organisation in rural and urban areas, at this time. The union won some major victories for its workers through militant actions. However, the ICU could not sustain itself, and in the late 1920s it collapsed.

Socialist organisations also began to organise black workers in the 1920s. The International Socialist League together with other socialist organisations formed the Communist Party in 1921. The Communist Party became the first non-racial political organisation in South Africa.

During the 1920s government policies became harsher and more racist. A colour-bar was established to stop blacks from holding semi-skilled jobs in some industries. It also meant that black workers were paid lower wages for unskilled work.

J.T. Gumede, was elected President of the ANC in 1927. He tried to revitalise the ANC in order to fight these racist policies. Gumede thought that the communists could make a contribution to this struggle and wanted the ANC to co-operate with them. However, in 1930, Gumede was voted out of office and the ANC became inactive in the 1930s undergo conservative leadership.

4. The ANC Gains New Life - 1940s

The ANC was boosted with new life and energy in the 1940s, which changed it from the careful organisation it was in the 1930s to the mass movement it was to become in the 1950s.

Increased attacks on the rights of black people and the rise of extreme Afrikaner nationalism created the need for a more militant response from the ANC. Harsher racism also brought greater co-operation between the organisations of Africans, Coloureds and Indians. In 1947, the ANC and the Indian Congresses signed a pact stating full support for one another`s campaigns.

In 1944 the ANC Youth League was formed. The young leaders of the Youth League - among them Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo - based their ideas on African nationalism. They believed Africans would be freed only by their own efforts. The Youth League aimed to involve the masses of people in militant struggles.

Many more people moved to the cities in the 1940s to work in new factories and industries. They began to from their own community organisations - such as the Squatter`s Movement - and trade unions. The militant ideas of the Youth League quickly found support among the new population of the cities. The Youth League drew up a Programme of Action calling for strikes, boycotts and defiance. It was adopted by the ANC in 1949, the year after the National party came to power. The Programme of Action led to the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s.

5. A Mass Movement is Born - 1950

The Defiance Campaign was the beginning of a mass movement of resistance to apartheid. apartheid aimed to separate the different race groups completely through laws like the Population Registration Act, Group areas Act and Bantu Education Act, and through stricter pass laws and forced removals.

"Non-Europeans" walked through "Europeans Only" entrances and demanded service at "White`s Only" counters of post offices. Africans broke the pass laws and Indian, Coloured and White "volunteers" entered African townships without permission.

The success of the Defiance Campaign encouraged further campaigns against apartheid laws, like the Group Areas Act and the Bantu Education Act.

The government tried to stop the Defiance Campaign by banning it`s leaders and passing new laws to prevent public disobedience. but the campaign had already made huge gains. It brought closer co-operation between the ANC and the SA Indian Congress, swelled their membership and also led to the formation of new organisations; the SA Coloured people`s Organisation (SACPO) and the Congress of Democrats (COD), an organisation of white democrats.

These organisations, together with the SA Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) formed the Congress Alliance.

The Congress Alliance came together to organise the Congress of the people - a conference of all the people of South Africa - which presented people`s demands for the kind of South Africa they wanted.

The demands called for the people to govern and for the land to be shared by those who work it. They called for houses, work, security and for free and equal education. These demands were drawn together into the Freedom Charter which was adopted at the Congress of the People at Kliptown on the 26th June 1955.

The government claimed that the Freedom Charter was a communist document. Communism had been banned by the government in 1950, so they arrested ANC and Congress leaders and brought them to trial in the famous Trason Trial. They also tried to prove that the ANC and its allies had a policy of violence and planned to overthrown the state.

In 1955 the government announced that women must carry passes. A huge campaign was mounted by women, countrywide. Women also led a militant campaign against municipal beerhalls. According to the law it was illegal for women to brew traditional beer. Police raided homes and destroyed home brewed liquor so that men would use municipal beerhalls. In response, women attacked the beerhalls and destroyed equipment and buildings. The women also organised a highly successful boycott of the beerhall.

There were many other community struggles in the 1950s. Resistance in the rural areas reached new heights. In many areas campaigns were led by the ANC against passes for women, forced removals and the Bantu Authorities Act. The Bantu Authorities Act gave the white government the power to remove chiefs they considered troublesome and replace them with those who would collaborate with the racist system.

The collaboration of chiefs with government officials was one of the causes of the Pondoland Revolt, a major event in the resistance by rural people. The Pondos also demanded representation in parliament, lower taxes and an end to Bantu Education.

The struggles of the 1950s brought blacks and whites together on a much greater scale in the fight for justice and democracy. The Congress Alliance was an expression of the ANC`s policy of non-racialism. This was expressed in the Freedom Charter which declared that South Africa belongs to all who live in it.

But not everyone in the ANC agreed with the policy of non- racialism. A small minority of members who called themselves Africanists, opposed the Freedom Charter. They objected to the ANC`s growing co-operation with whites and Indians, who they described as foreigners. They were also suspicious of communists who, they felt, brought a foreign ideology into the struggle.

The differences between the Africanists and those in the ANC who supported non-racialism, could not be overcome. In 1959 the Africanists broke away and formed the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Anti-pass campaigns were taken up by both the ANC and the PAC in 1960.

The PAC campaign began on the 21st March. People were asked to leave their passes at home and gather at police stations to be arrested. People gathered in large numbers at Sharpville in the Vaal and at Nyanga and Langa near Cape Town. At Sharpville the police opened fire on the unarmed and peaceful crowd, killing 69 and wounding 186.

The massacre of peaceful protestors at Sharpville brought a decade of peaceful protest to an end. On 30 March 1960, ten days after the Sharpville massacre, the government banned the ANC and the PAC. They declared a state of emergency and arrested thousands of Congress and PAC activists.

6. The Armed Struggle Begins - 1960s

The ANC took up arms against the South African Government in 1961. The massacre of peaceful protestors and the subsequent banning of the ANC made it clear that peaceful protest alone would not force the regime to change. The ANC went underground and continued to organise secretly. Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was formed to "hit back by all means within our power in defence of our people, our future and our freedom"

In 18 months MK carried out 200 acts of sabotage. But the underground organisation was no match for the regime, which began to use even harsher methods of repression. Laws were passed to make death the penalty for sabotage and to allow police to detain people for 90 days without trial. in 1963, police raided the secret headquarters of MK, arresting the leadership. This led to the Rivonia Trial where the leaders of MK were charged with attempting to cause a violent revolution.

Some ANC leaders - among them Oliver Tambo and Joe Slovo avoided arrest and left the country. Other ANC members left to undergo military training.

After the Rivonia Trial, the underground structures of the ANC in the country were all but destroyed. The ANC was faced with the question of how to bring trained soldiers back into the country to continue the struggle. However, South Africa was surrounded by countries that were very hostile to the ANC. Rhodesia, Angola and Mozambique were all controlled by colonial governments that supported the regime. MK would first have to make its way through those countries before it could reach home ground.

In 1967, MK began a joint campaign with Zapu, a people`s army fighting for the liberation of Zimbabwe. They aimed to find a route into South Africa by first crossing the Zambezi River from Zambia and into Zimbabwe, then marching across Zimbabwe through Wankie Game reserve, and crossing the Limpopo River into South Africa. While the Wankie Campaign gave MK cadres important experience in combat, it was clear that MK would have to find other ways of getting into the country. The ANC consultative conference at Morogoro, Tanzania in 1969 looked for solutions to this problem.

The Morogoro Conference called for an all-round struggle. Both armed struggle and mass political struggle had to be used to defeat the enemy. But the armed struggle and the revival of mass struggle depended on building ANC underground structures within the country. A fourth aspect of the all-round struggle was the campaign for international support and assistance from the rest of the world. These four aspects were often called the four pillars of struggle. The non-racial character of the ANC was further consolidated by the opening up of the ANC membership to non-Africans.

7. Workers and Students Fight Back - 1970s

During the 1960s, as a result of the banning of the liberation movement, there were few signs of resistance. The apartheid system grew stronger and extended its control over all aspects of people`s lives. But, despite the lull, people were not prepared to accept the hardships and oppression of apartheid. In the 1970s workers and students fought back against the system. their struggles changed the face of South Africa.

From about 1970 prices began to rise sharply, making it even more difficult for workers to survive on low wages. Spontaneous strikes resulted: workers walked off the job demanding wage increases. The strike began in Durban in 1973 and later spread to other parts of the country.

Student anger and grievances against bantu education exploded in June 1976. Tens of thousands of high school students took to the streets to protest against compulsory use of Afrikaans at schools. Police opened fire on marching students, killing thirteen year old Hector Petersen and at least three others. This began an uprising that spread to other parts of the country leaving over 1,000 dead, most of whom were killed by the police.

Many Soweto student leaders were influenced by the ideas of black consciousness. The South African Students Movement (SASM), one of the first organisations of black high school students, played an important role in the 1976 uprising. There were also small groups of student activists who were linked to old ANC members and the ANC underground. ANC underground structures issued pamphlets calling on the community to support students and linking the student struggle to the struggle for national liberation

8. The Struggle for People`s Power - 1980s

In the 1980s, people took the liberation struggle to new heights. In the workplace, in the community and in the schools, the people aimed to take control of their situation. All areas of life became areas of political struggle. These strugglers were linked to the demand for political power.

Thousands of youths flooded the ranks of MK after the 1976 uprising. The violence used by the security forces to quell the uprising made the youths determined to come back and fight. The 1976 uprising also led the regime to change its strategy. For the first time reforms were introduced to apartheid. These aimed to win some support from the black community, but without making substantial changes. at the same time the military was greatly strengthened. They could use greater force and repression against people and organisations who ere considered revolutionary. Through the State Security Council and a network of other structures, the military also gained control over the most important decisions of government. This combination of reform and repression, the NP government described as winning the hearts and minds of black South Africans.

However, the reforms proposed by the government, such as the Tricameral Parliament and Black Local Authorities in African Townships, were totally rejected and only gave rise to greater resistance.

In the 1980s community organisations such as civics, students and youth organisations and women`s structures began to spring up all over South Africa. This was a rebirth of the mass Congress movement and led to the formation of the United Democratic Front.

One of the biggest organisations formed at this time was the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) with branches in towns and cities throughout South Africa. In many cases civic organisations developed out of parent - student committees which had been formed to support education struggles. Massive national school boycotts rocked the townships in 1980 and again in 1984/5.

Worker organisation and power also took a major step forward with the formation of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985. Cosatu drew together independent unions that had begun to grow in the seventies. Cosatu committed itself to advancing the struggles of workers both in the workplace and in the community. 1987 saw the highest number of strikes ever, including a strike by over 300,000 mineworkers.

In 1985, the ANC called on township residents to make townships ungovernable by destroying the Black Local Authorities. Councillors and police were called on to resign. Municipal buildings and homes of collaborators were attacked. As the administrative system broke down, people established their own democratic structures to run the community, including street committees and people`s courts. An atmosphere of mass insurrection prevailed in many townships and rural towns across the country during 1985 and 1986. Mass struggles and the armed struggle began to support one another. Troops and police who had moved into the townships at the end of 1984 engaged in running battles with youths - armed with stones and petrol bombs - in an effort to re-establish control.

As resistance mounted, the regime became more vicious. A state of emergency was declared over many parts of the country in July 1985. It lasted for six months, and then in June 1986 a national emergency was declared, that lasted until 1990. The states of emergency were used to detain over 300,000 people, among them children, and to ban the UDF and its affiliates from all activity. Cosatu was restricted from political activity.

Secret government units killed activists and bombed their homes. The South African Defence Force (SADF) led raids into neighbouring countries to destroy ANC bases. These raids were part of a general strategy to destabilise neighbouring governments that offered the ANC support. The South African government gave extensive support to bandit organisations like Renamo in Mozambique and Unita in Angola.

The struggle for people`s power in the 1980s shook the foundations of the bantustan system. The regime tried desperately to save it by supporting vigilante groups and suppressing popular resistance.

In Natal, the struggle for people`s power was met with violence by Inkatha warlords who were opposed to the growth of community organisations. civic and youth organisations and Cosatu were opposed to the undemocratic practices of Inkatha and its ties to the KwaZulu government. The conflict has led to a bitter war in Natal, where thousands have lost their lives. Today there is evidence that the apartheid government gave money to Inkatha to fight the ANC, and that the South African Police and the KwaZulu Police have played active roles in this war.

9. The ANC is Unbanned

In spite of detentions and bannings, the mass movement took to the city streets defiantly with the ANC and SACP flags and banners. The people proclaimed the ANC unbanned. In February 1990, the regime was forced to unban the ANC and other organisations.

By unbanning the ANC, the regime indicated for the first time, that it might be prepared to try and solve South Africa`s problems peacefully, through negotiations.

After its unbanning the ANC began to establish branch and regional structures of its members. Regional and national membership was elected. At its national conference inside the country since 1959, the ANC restated its aim to unite South Africa and bring the country to free and democratic elections.

At the 1991 National Conference of the ANC Nelson Mandela was elected President. Oliver Tambo, who served as President from 1969 to 1991 was elected National Chairperson. Tambo died in April 1993 after serving the ANC his entire adult life.

The negotiations initiated by the ANC resulted in the holding of historic first elections based on one person one vote in April 1994.

The ANC won these first historic elections with a vast majority. 62,6% of the more than 22 million votes cast were in favour of the ANC.

On the 10th of May 1994 Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the President of South Africa. The ANC has been in power ever since

http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=206

The Power of One (Original Theatrical Trailer)

A Movie about the Power of Words, and how this little boy used them to help those African people to speak for them selves, and how to express their desire for freedom and dependence from the White man, who took their lands and forced them to follow his rules.

الجمعة، 5 ديسمبر 2014

South Africa: White domination and Black resistance (1881-1948)

South Africa: White domination and Black resistance (1881-1948)

Updated February 2011

The discovery of diamonds in Griqualand West led to annexation of the territory by Britian in 1871; by 1880 diamonds had overtaken wool as the Cape's major export by value and they became a major source of revenue for the Cape government (Newbury 1989, 11, 13, 18; Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 21). The diamond fields attracted adventurers from Britain, Europe and USA as well as African migrant workers from across eastern seaboard and stimulated agricultural market production in the region (Newbury 1989, 19).

Profits generated from the diamond fields provided the capital to develop the gold mining industry after gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1885; profits from the mining industry in turn were reinvested in finance and industry, driving economic growth and economic diversification (Lewis 1990, 29-30; Makhura 1995, 258; Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 21). The developments in the interior stimulated the rollout of rail infrastructure so that by 1892 the Witwatersrand was connected with Cape Town and by 1895 with Delgoa Bay; by 1910 an extensive network covering South Africa had been laid out (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 21; Jones 1996; Spoornet 2007).

Gold provided the ZAR with the revenue required to subjugate the remaining independent chiefdoms and develop its governmental infrastructure, but also presented the threat of the Boers being swamped by foreign immigrants and attempts by President Kruger to resist settlers' demands for the franchise led to conflict (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 21, 22; Makhura 1995, 258, 261, 266). In the Orange Free State and the ZAR the franchise was restricted to Boers and Africans were subjected to labour tribute, cattle extractions, taxation and land alienation (Makhura 1995, 259; Morton 1992, 112; Malkin 2008, 91).

In Natal a system of indirect rule through chiefs was implemented, Africans were restricted to "native reserves" to free up land for occupation by White farmers and heavy taxes were imposed to secure wage labour (Malkin 2008, 30, 91; McClendon 2004, 342, 343, 356; Etherington 1978, 9). In 1864 the Legislative Council effectively restricted the franchise to the small minority of White settlers in the Colony so that by 1909 only 150 Indians and six Africans qualified to vote out of a total electorate of 24 000 voters (Evans & Philips 2001, 94, 97).

In the Cape liberal notions of incorporating and assimilating Africans culturally and politically gave way to a Social Darwinism that believed that "it was only a matter of time before 'the lower races, those whom we designate as savages, must disappear from the face of the earth'" (Parry 1983, 380; Beinart 2001, 71). Under Prime Minister Cecil John Rhodes, in 1887 and 1892, the Legislative Council adopted legislation to reduce African enfranchisement by raising property qualifications and adding a literacy test (Parry 1983, 384; Malkin 2008, 25, 26). Administrative control over Africans was tightened through local government structures dominated by traditional authorities and to coerse Africans to take up wage labour employment in mining and commercial farming (Malkin 2008, 91; Parry 1983, 380, 385-387).

African resistance continued in various forms. Instances include the Ndzundza Ndebele rebellion of 1882, that of the Bagananwa in 1894 and the Bhambada Rebellion of 1906 (Makhura 1995, 259, 263, 267; Beinart 2001, 97-99, 101). New directions were taken by the educated African elite with the founding of the first African political group in the Eastern Cape, Imbumba ya Manyama (Union of the Blacks) in the 1880s, which articulated an African identity that transcended tribalism, and the formation of the first African separationist Church of Africa in 1898 by the Rev PJ Mzimba (Williams 1970, 373, 381). Strategies to push Africans into wage labour in the Cape and Natal through taxation payable in cash were not initially successful for many peasants proved to be resilient and flexible by adopting innovations such as plows and wagons, crop diversification and market production that generated the cash needed to pay taxes and purchase capital and consumer goods; migrant labour was thus a short term resort to raise funds for bride-wealth, to purchase capital goods to expand agricultural production or purchase guns to repel White intrusions (Beinart 2001, 22-25; Lewis 1984, 1, 2, 12-14, 22-24; Etherington 1978, 2-4, 6).

From 1860 onwards, as a result of labour shortages, Indians were imported as indentured labourers to work the sugar fields of Natal, half of whom elected to remain there, and these were followed by traders and merchants so that by 1910 there were about 152 000 Indians in South Africa (Malkin 2008, 117, 120, 121). After gaining self government in 1893 White settlers in Natal began hedging the Indian community about with discriminatory legislation as did the ZAR and the Oragne Free State (Malkin 2008, 121-125). From 1894 Mohandas Gandhi began organizing Indian communities to engae in campaigns of passive resistance that wrung concessions from the authorities (Malkin 2008, 128-132).

Relations between Britain and the ZAR deteriorated rapidly and war broke out on 11 October 1899, into which the Orange Free State was drawn by treaty obligations (Williams 2006, 5, 6; Malkin 2008, 8, 34, 36). As a result of the guerrilla warfare strategies adopted by the the Boers and the brutal scorched earth and concentration camp responses of the British, the war was drawn out, bloody and expensive (Williams 2006, 15-17; Malkin 2008, 9, 36, 45). By the end of the war 400 000 British soldiers were deployed in South Africa, 2000 had been killed and 20 000 wounded; 4000 Boer troops were killed 115 000 civilians had been incarcerated in concentration camps where 27 027 perished as a result of callous neglect, as did 16 000 of the 116 000 Africans interned by the British, and millions of South Africans of all races were reduced to penury (Williams 2006, 18; Malkin 2008, 45).

Despite the great suffering experienced the four colonies drew together in a Convention in 1908 that drew up a constitution for a union that was consummated, with the approval of the British Parliament by the South Africa Act of 1909, in 1910 (Williams 2006, 7; Malkin 2008, 68). The Convention, an all male, all White affair, was agreed on securing "the just predominance of the white races [ie Dutch and English]" (Beinart 2001, 89) and differed primarily on what franchise arrangements would best secure this outcome; they arrived at a compromise that left all provinces but the Cape with an unqualified white male franchise, while the Cape retained a colour-blind but heavily qualified franchise that enabled 10% of Coloureds and 5% Africans to vote (Malkin 2008, 22, 74, 98; Evans & Philips 2001, 94. See also Historical franchise arrangements).

The economy of the Union was heavily dependent on foreign trade, particularly on gold, diamonds and agricultural exports and on capital inflows to finance the development of the mining industry and transport infrastructure, but while manufacturing formed less than 7% of national income, financial and banking institutions were relatively well developed (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 23). Infrastructure investment and the war left the Union saddled with a heavy public debt burden of 96% of national income and though the ratio fluctuated it remained high, being 88% in 1945 (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 23, 31). Education levels were low, for the generation of Whites born in 1885 had only eight years of schooling on average and other races less than two (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 23).

Average annual GDP growth was high between 1919-1949 (5% in 1919-1929, 5.8% in 1929-1949. Lewis 1990, 24). The proportion of national income derived from agriculture declined from 17.4% in 1911 to 13% in 1946, while that of manufacturing rose from 6.7% to 21.3% and mining's share fluctuated, but overall declined from a high of 27.1% in 1911 to 11.9% in 1946 (Lewis 1990, 25). The rise in manufacturing reflected considerable diversification of the economy away from primary production and was stimulated by measures taken by succesive governments to encourage import substitution, state investment in steel, electricity and communication services and was further boosted by the dampening effects of the First and Second World Wars on international trade (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 26). Despite this, the economy remained open and was heavily dependent on the import of raw materials for manufacturing and the export of primary products to secure the foreign exchange (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 26). Large scale intervention by the state in agriculture in a variety of ways, however, distorted resource allocation and created economic inefficiencies, the costs of which were born by the taxpayer (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 27, 28).

Between 1911 and 1945 the population of South Africa grew by 2% per year on average; the white population peaked as proportion of total population around 1921 at just under 22% and declined marginally until 1951 when it was 20.9%, while the African proportion rose marginally in the same period from 67.2% to 67.6% (Lewis 1990, 22, 23; Beinart 2001, 353). The ability of whites to maintain their share of the population was due to immigration from Europe, especially the UK (Lewis 1990, 22). Population urbanization, at 25% in 1911, rose steadily to 32% by 1936 and by 1951 reached 43%; Africans lagged other population groups and remained primarily rural, increasing from 13% in 1911 to 27% in 1951 (Beinart 2001, 355). The percentage of national income for Whites was 75% in 1917 and declined marginally to 73.6% by 1946 and, while the share of Coloureds and Indians stagnated, that of Africans improved from 17.9 in 1924 to 20.2% in 1946 (Lewis 1990, 39).

By 1911 about 26% of Africans in the Union were Christians and many had been exposed to varying degrees of missionary education (Elphick 1997, 247). The small but growing educated African elite viewed the South Africa Act as a betrayal, especially since Africans had generally supported the British war effort and many thousands had served in the British army (Malkin 2008, 40). The Mines and Works Act and the Native Labour Regulation Act, passed in 1911, privileged White and Coloured workers by reserving jobs on the mines and railways for them and tightened up the control of African workers in the urban areas through stricter pass regulations (Lipton 1986, 109; Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 29). Thus, from early on it was clear to African intellectuals that political power would be used by Whites to advance their economic position at the expense of Africans.

In 1912 representatives of various African associations, professionals, intellectuals, churchmen and members of the traditional aristocracy launched the South African Native National Congress (SANNC, renamed the African National Congress, ANC, in 1923) in Bloemfontein, to unite Africans in resistance to racism and exploitation and to engage the South African Party (SAP) government to redress African grievances (Malkin 2008, 98; South African History Online 2006; South African History Online Undateda). The organisation was elitist in composition, liberal in ideology, emphasized obedience to the law and non-confrontationist; it proved to be rather ineffectual since it had no mass base and no strategy by which it could force itself on the attention of the authorities (Malkin 2008, 99; South African History Online Undateda).

The impotence of the SANNC was vividly demonstrated by the passage of the Natives Land Act of 1913, for their representations to the SAP government and to Britain were ignored (Beinart 2001, 57). Though not immediately implemented throughout the country, the Act formalised land alienation by Whites, stripped Africans of land rights outside of the seven percent of land designated as reserves for them and made the substantial class of tenant farmers, share croppers and labourers (estimated at about one third of Africans at that time) on White land vulnerable to increased extractions and arbitrary eviction by farmers, while sharecropping itself was abolished (Beinart 2001, 53-57; Malkin 2008, 82). The implementation of the Act was slow and uneven, but it was increasingly used on farms to undercut the bargaining power of Africans, restrict their mobility and reduce them to servility (Beinart 2001, 58). Many Africans were forced off the land into the overcrowded reserves without access to land and so driven to migrant labour (Malkin 2008, 82). The Native Urban Areas Act was passed in 1923 to create segregated residential areas for Africans, set in place administrative machinery to enable tighter control of Africans through application of pass laws and effect the expulsion of "surplus" Africans from the towns and cities (Malkin 2008, 142, 143; South African History Online 2006).

The entry of South Africa into the First World War in August 1914 on the side of Britain reopened the wounds of the South African War and provoked a rebellion by some Afrikaaners; its ruthless suppression by the SAP government gave fresh impetus to the Afrikaaner nationalism that had emerged in the Cape in the nineteenth century and found its political articulation in the National Party that had been formed in January 1914 (Beinart 2001, 80; Malkin 2008, 113; Du Toit 1970, 540, 541). The movement strove for language equality with English, the upliftment of the substantial class of empoverished (primarily Afrikaans) Whites, a "Christian National" education system and substantive independence of South Africa from Britain (Beinart 2001, 80-82).

The White working class become increasingly militant as a result of the brutal fashion in which the SAP government suppressed the 1913/4 general strike, leading to the founding of the Communist party of South Africa (CPSA) in 1921 (Beinart 2001, 83-84; Innes & Plaut 1978, 56). African migrant workers, following the lead of White workers, became more militant and organised and strikes occurred after the war; a strike of 70 000 mine workers occurred in 1919/20 that was suppressed with troops, and the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) emerged in 1919 in Cape Town to lead a strike of dock workers in that year (South African History Online 2006; Innes & Plaut 1978, 56). Faced with rising costs and a fixed gold price, mining companies attempted to reduce labour costs through mechanisation and deskilling to replace higher paid skilled White workers with lower paid semi-skilled African workers and White women, which led to labour unrest that culminated the 1922 revolt of White workers on the Witwatersrand that was crushed by Prime Minister Jan Smuts using military force (Innes & Plaut 1978, 56, 58; Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 25).

In 1920 South Africa received South West Africa, which it had seized from the Germans in 1915, as League of Nations Class C Mandate allowing it to administer the territory as if it were a fifth province (History of Nations 2004). An alliance between the Afrikaaner nationalist National Party (NP) and the Labour Party was victorious in the 1924 election and they began implementing measures to advance the position of White workers at the expense of Africans by excluding Africans from employment in the new parastatal corporations and from labour dispute resolution mechanisms while reserving certain categories of work exclusively for whites, but the victory of the mine owners was not reversed and the earnings of white miners deteriorated (Innes & Plaut 1978, 57, 58; Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 25, 29).

The ICU increasingly took on the character of a popularist, even rural, protest movement, peaking in membership at about 100 000 in 1927, but declined rapidly thereafter as a result of regional factionalism, while in some economic sectors white trade unionist activists and the CPSA became involved in unionising African workers, and joint strike action became common; by 1928 the CPSA was calling for a "Native Republic" (Innes & Plaut 1978, 58; Beinart 2001, 104, 105). In response to the new threat, the Native Administration Act of 1927 and the Riotous Assemblies (Amendment) Act of 1930 were passed, giving sweeping powers to the police that were used to assault, imprison and murder workers and activists, so that by 1932 the ICU was destroyed, the CPSA and African trade unions cowered into inactivity and white workers detached from the mainstream of the labour movement (Innes & Plaut 1978, 59).

The Afrikaaner nationalists were able to quickly attain their initial objectives: Dutch was replaced with Afrikaans as an official language in 1925, the Imperial Conference 1926 was used to obtain Dominion status for South Africa that was then used as a springboard for legislating substantive independence from Britain, a South African flag was adopted in 1928 in place of the Union Jack and Die Stem was played alongside God Save the Queen from 1934 onwards (Beinart 2001, 114, 115). They worked diligently at reducing the significance of the non-White franchise; in 1930 all franchise qualifications for adult White men in the Cape (but not for other groups) were abolished and all adult White women in the Union were given the vote, but no women of colour (Beinart 2001, 115, 116).

South Africa recovered quickly from the Great Depression, after abandoning the gold standard in 1930, and it entered into a period of higher economic growth, driven primarily by a substantially higher gold price, but cheap African labour (real wages remained between 1911 and 1962), international price deflation and government unemployment handouts and subsidies also played a role (Fedderke & Simkins 2006, 25, 27, 30; Innes & Plaut 1978, 58). The high gold price made significant taxation of the mining industry possible for the first time and gold revenue rose from 6% of total state revenue in 1925 to 30% in 1933, thus enabling spending on unemployed White workers, on White farmers affected by the collapse of commodity prices and on subsidies to industries affected by the depression possible (Beinart 2001, 118, 119; Innes & Plaut 1978, 58). Rapidly expanding industry as a result of inward industrialisation led to increased work opportunities for Whites and reduced poverty amongst them substantially (Beinart 2001, 118, 119).

The crisis created by the depression, the attainment of the main Afrikaaner nationalist objectives and the substantial agreement between the NP and the SAP over race issues, facilitated their unification as the South African United National Party (called the United Party or UP) in 1934 and the breakaway Purified National Party (GNP), which aimed at obtaining a republic, fared poorly in elections of 1938 (Beinart 2001, 117). In 1936 the UP used wielded its overwhelming majority to amend the entrenched franchise clauses in the constitution and removed African's from the common voters' roll in the Cape, placing them on a separate roll that elected three white MPs and four white senators to Parliament and established a advisory Native Representative Council for the Union that had no powers (Malkin 2008, 143; Evans & Philips 2001, 91).

Segregation was further advanced by the passage of the Development Trust and Land Act later in the year that enabled the transfer of further land to Africans (which eventually rose to 13% of South Africa's territory), but empowered the dispossession of African farmers of land they owned privately and increased further the power of white farmers in negotiating tenancy arrangements (Beinart 2001, 123, 124; South African history Online 2006). Furthermore, labour law amendments enforced the segregation of trade unions, in 1937 Africans were prohibited from acquiring land in the urban areas without the consent of the Governor-General and the operation of the pass laws were extended to women (South African history Online 2006).

Parliament's decision to take South Africa into the Second World War on the side of Britain reopened the wounds of 1899 and 1914 and split the government, the United Party and the Afrikaaner people (Beinart 2001, 121). The war greatly accelerated industrial expansion and diversification and population urbanisation, especially that of Africans (Beinart 2001, 130). With large sections of the White male population away fighting, and rapidly expanding labour needs, the increasingly important manufacturing sector for pressed for a settled rather than migrant African labour force; the UP government began to relax the implementation of the pass laws, attempted to win Africans over to the war effort and to take seriously for the first time the possibility of a permanently settled African urban population with all the attendant social and political implications (Beinart 2001, 129, 130). The CPSA organised the African Mineworkers Union (AMU) in 1941 and other unions for African workers emerged and expanded rapidly; in 1946 the AMU launched the largest and most prolonged strike experienced in South Africa hitherto, but Smuts suppressed the strike with soldiers and the AMU was suppressed (Beinart 2001, 131). Social protest reemerged during the War in the form of bus boycotts and squatter movements and the ANC, reinvigorated by the formation of the militant ANC Youth Wing in 1946, became increasingly orientated towards more radical mass action (Beinart 2001, 132-134).

Radical Afrikaaner organisations emerged during the war that mobilised nationalists across the country, the Reunited National Party (HNP; the GNP plus defectors from the UP) made gains in the 1943 election and concern spread amongst Whites in the post-war period that the openness that had been permitted had undermined White power and security (Beinart 2001, 121; Dubow 1992, 211, 216). By exploiting these fears the HNP and its ally the Afrikaaner Party narrowly won the election of 1948 by campaigning on the slogan "apartheid ("seperateness"), obtaining between them 55.7% of the seats in the House of Assembly with only 41.6% of the votes as a result of the peculiarities of the South African single member plurality system (Nohlen et al 1999, 818, 831, 836).

References

BEINART, W 2001Twentieth-century South Africa, Oxfrord University Press.

DUBOW, S 1992 "Afrikaner Nationalism, Apartheid and the Conceptualization of 'Race'", Journal of African History, 33(2), 209-237, [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/182999 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

DU TOIT, BM 1970 "Afrikaners, Nationalists, and Apartheid", Journal of Modern African Studies, 8(4), December, 531-551, [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/159088 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

ELPHICK, R 1997 "The benevolent Empire and the Social Gospel" IN Elphick, R & Davenport, R (eds), Christianity in Southern Africa: A Political, Social & Cultural History, David Philip.

ETHERINGTON, N 1978 "African Economic Experiments in Colonial Natal 1845-1880", African Economic History, 5, Spring, 1-15, [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/3601437 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

EVANS, J & PHILIPS, D 2001 "'Where there is no safety in numbers': fear and the franchise in South Africa - the case of Natal" IN Kirkby, D & Coleborne, C (eds) Law, history, colonialism: the reach of empire, Manchester University Press.

FEDDERKE, J & SIMKINS, C 2006 "Economic Growth in South Africa since the Late Nineteenth Century", Working Paper.

HISTORY OF NATIONS 2004 "History of Namibia", [www] http://www.historyofnations.net/africa/namibia.html [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

INNES, D & PLAUT, M 1978, "Class Struggle and the State", Review of African Political Economy, 11, 51-61, [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/3997965 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

JONES, HM 1996 "The Delagoa Bay Railway and the origin of Steinaecker's Horse", Military History Journal, 10(3), June, [www] http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol103jo.html [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

LEWIS, J 1984 "The Rise and Fall of the South African Peasantry: A Critique and Reassessment", Journal of Southern African Studies, 11(1), October, 1-24, [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/2636544 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

LEWIS, SR 1990 The economics of apartheid, Council on Foreign Relations.

LIPTON, M 1986 Capitalism and apartheid, Rowman and Allanheld.

MALKIN, E 2008 Imperialism, White Nationalism, and Race: South Africa, 1902-1914, BA(Hons) Thesis, Wesleyan University Connecticut, http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1120&context=etd_hon_theses [PDF document, opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010).

NEWBURY, CW 1989 The diamond ring: business, politics, and precious stones in South Africa, 1867-1947, Oxford University Press.

MCCLENDON, T 2004 "The Man Who Would Be Inkosi: Civilising Missions in Shepstone's Early Career", Journal of Southern African Studies, 30(2), June, 339-358 [www] http://www.jstor.org/stable/4133839 [opens new window] (accessed 10 Mar 2010)